Photo of Alicia Dietz by Maj. Richelle Treece, US Army National Guard.

In honor of Women’s History Month, Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (HCCC) is participating in #5womenartists, a national campaign led by The National Museum of Women in the Arts to share information about women artists.

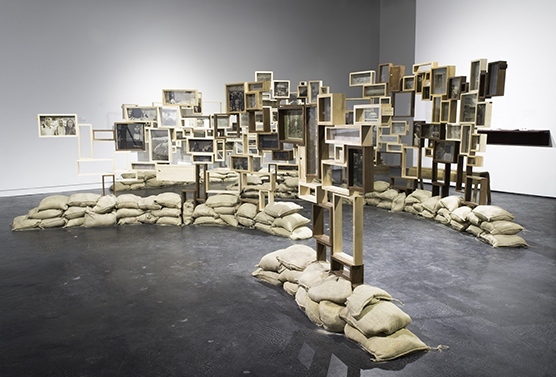

HCCC Curator Kathryn Hall recently asked woodworker and veteran, Alicia Dietz, currently featured in United by Hand: Work and Service by Drew Cameron, Alicia Dietz, and Ehren Tool, a few questions about her experience as a woodworker and Officer in the U.S. Army.

KH: As a female woodworker and Officer in the U.S. Army, you have chosen two male-dominated professions. Could you speak about your experience as a minority in your field? How has your identity influenced your work?

AD: I’ve always thought of myself as a soldier first and a female soldier second. I guess I still do. When I was a brand-new “butter bar” (Second Lieutenant – the lowest officer rank in the Army), my unit was in Iraq. My first flight beyond the confines of the Alabama training was over Baghdad. But long before I climbed in the cockpit, I climbed onto the top of the Blackhawk, sat on the rotor hub, and assisted my crew chiefs while they adjusted the PC links. We were up there for hours. They were nearing the end of their duty day, and the First Sergeant wanted to extend them, something that was happening routinely. We didn’t need the aircraft for a mission the following morning, so I overrode that decision, and we called it quits for the day. That evening, I became “Mamma Dietz.” The name stuck. Through 10 years, seven positions, and two company commands, that same leadership style was born from a desire to protect my soldiers, while still accomplishing the mission. Maybe this was because I was a female leader, maybe not.

When I got to Vermont Woodworking School, I was again surrounded by men. In my second semester, I took on a seven-foot dresser. I just hung up a sign that said, “The man who says it can’t be done should not interrupt the woman doing it.” Then, I spent the next 15 weeks building a mountain dresser with a topographical map of Denali and the Alaskan Range carved into the front.

Maybe it will be because of your gender or your race or your sexuality. Maybe it will be because of who you hang out with or where you were born. Maybe it will be because of the language you speak or the religion you keep. No matter the reason, there will always be doubters—those who think you can’t do it. Working in a male-dominated field for most of my adult life, I’ve learned that, while there are certainly doubters, supporters outweigh them. Be who you are, and do so proudly. I’ve been lucky enough to surround myself with people who embrace the passion I have for leading, flying, and creating.

KH: Do you have a female role model that has inspired you and your career? If you do, how has this person influenced your life?

AD: As a woodworker, hands down and without a doubt, it’s Wendy Maruyama who’s had the biggest influence. I sought out an internship with her during woodworking school, because I saw in her work what I hope to someday accomplish in mine: her use of craft as a vehicle to educate, empower, and show the humanity (or lack thereof) in our society. Maya Angelou said, “My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.” I’m convinced she had Wendy in mind when she said this.

At the end of my internship, I had to write a paper on what I had learned. I think it is really the best way to summarize the impact Wendy had on me. As I noted in my paper, she taught me the following lessons:

- There is more than one way to design.

- Know the broad sense, have some strategy, and embrace surprises and mistakes.

- Multi-tasking is an efficient way of producing.

- Small projects are their own reward.

- Experiment, experiment, experiment. (Wendy is a proponent of experimentation in the way that the Pope is a proponent of religion. I learned this lesson on the first day, and I have carried that with me ever since. Even if I try one thing today, I will try something new tomorrow. )

- And, laughter makes the days enjoyable and the years memorable.

I learned just as much from Wendy as a person as I did from her as a woodworker. And, believe me, both are tremendous.

KH: Looking at the stories that you present in Collective Cadence and Reintegration/Conveyance, it is evident that narrative is an essential component in your work as you relay the stories of many individuals. I think that one can argue that a narrative also lies in the growing list of names in Fallen Soldiers that memorializes those who have fallen in Iraq and Afghanistan. What have you learned from the stories that you have collected? Recognizing that it can be difficult for veterans to speak about their military experiences, what advice would you give to someone who desires to connect with a family member or friend who has served?

AD: I’ve been reminded that there is a story in each of us. Through this project, I have learned that, while we may experience something personally and might feel that we are alone in our own experience, there are so many others who’ve had parallel experiences. That we are individuals, and that we are part of a collective at the same time. In The Spirituality of Imperfection, Ernest Kurtz says, “… shared storytelling creates community… When we tell our own stories, we gain respect and listen to others; to listen to others enables us to tell our own.” In this spirit, the shared story of the veteran experience is my new mission. Each time I make a finely crafted box that encapsulates a veteran’s story, I preserve that memory and give it new voice. These experiences are often hidden from the public. While concealment on the battlefield is a survival skill, concealment off the battlefield could have the opposite effect. Transparency becomes essential to survival. It is important to our own survival to share our stories. So, I make to communicate.

It can be hard to know how to talk to a family member. I think it all starts with honesty and a genuine interest. And time. There is a concept in interviewing that proposes that some of the most insightful and deepest conversation comes in those times between questions, when the recorder is off, and the person feels like they are in a safe place. Not everyone will want to share their story. For me, simply knowing that someone would want to hear me when I am ready to talk is such a comfort and could be the catalyst somewhere down the road.

For me, when an experience only lives in my head, it takes on a life of its own. I have little control over it. But, when I put the words down onto paper, they become more tangible. It sounds strange, but this seemingly simple act of physically writing out an experience can shift the power and control from the experience back to me. When the words go on the page, I can put that burden onto someone else, some other character, or just out into the universe. I can share those words and not feel so singular. Even before anyone has read them, I am somehow part of a community of people.

When I was collecting stories, one of my friends wrote to me after about four months. He said that he was sorry it took him so long to respond. But that it took him that long to get the words out of his head and onto paper. And, when he did, he felt this sense of relief, of release, and of some solitude. The story allowed him to move past the sheer emotion and feel more in control again.

KH: The Collective Cadence archive is ongoing. Could you tell us how others can submit their stories? How can individuals stay up to date with the archive as it grows?

AD: The Collective Cadence Project is a community bound by the stories that shape the fabric of our experience and the idea that, as soldiers, we were part of something much bigger than ourselves.

Through the telling of each, we are united as one. In the telling of the collective, we find our own.

Please join us in sharing this experience. All words remain original to each storyteller; merely, the form is changed.

Creating a safe environment is my primary concern. Some stories are anonymous. Others were submitted to the project to provide a release for the teller but are now housed in closed boxes that cannot be opened. I respect how you would like your story to be told.

If you are interested in submitting an essay for inclusion in the art piece and the community, please email or contact me through collectivecadenceproject@gmail.com. You can follow the project and read excerpts of stories on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/collectivecadenceproject/

About Alicia Dietz

Alicia Dietz (Richmond, VA) is a woodworker and Iraq War veteran. From 2001 – 2011, she served in combat and peace-keeping operations as a U.S. Army Officer, UH-60 Blackhawk Helicopter Pilot, Maintenance Test Pilot, and Company Commander of over 125 soldiers. In 2015, Dietz received an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University in furniture design and woodworking. She maintains two woodworking and furniture degrees from Vermont Woodworking School in 2013 and 2012 and a BSJ in advertising/journalism, from Ohio University, in 2001. Her work has been exhibited at the Center for Art in Wood (Philadelphia, PA), Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA), and Arrowmont School of Crafts (Gatlinburg, TN), among others. More information at https://aliciadietzstudios.com.