By Betsy Huete

About a year ago, there was a big blow-up all over my Facebook feed about a taco truck in Portland. The women who ran the truck sold shrimp tacos inspired by the tacos in a restaurant in a tourist town in Mexico. Apparently, the women had eaten shrimp tacos while vacationing there, and because they were so impressed, they peeked into the kitchen to see how the chef made them. They took those techniques and what they could make of the recipe home with them to Portland, and their version sold really well. I can’t remember if they outright admitted their Mexico restaurant experience in an interview, or if someone figured out, but soon the denizens of Portland discovered the Mexico connection and were appalled. There were protests, and articles — tons of bad press — which forced the women and their shrimp tacos out of business.

Regardless how one may feel about cultural appropriation and intellectual property, this version of cancel/call-out culture may come off a bit puritanical to many Texans — particularly Houstonians — who enjoy the bounty of different cultures and ethnic food, and the mish-mashing together of ethnic food cultures.

But no culinary tradition has been more appropriated by Texans than Mexican food — so much so that over time, the mix became its own entity: Tex-Mex. The provenance lines are so blurred between what is Texan and what is Mexican that there are regular disputes about what kind of Tex-Mex originated in what part of Texas.

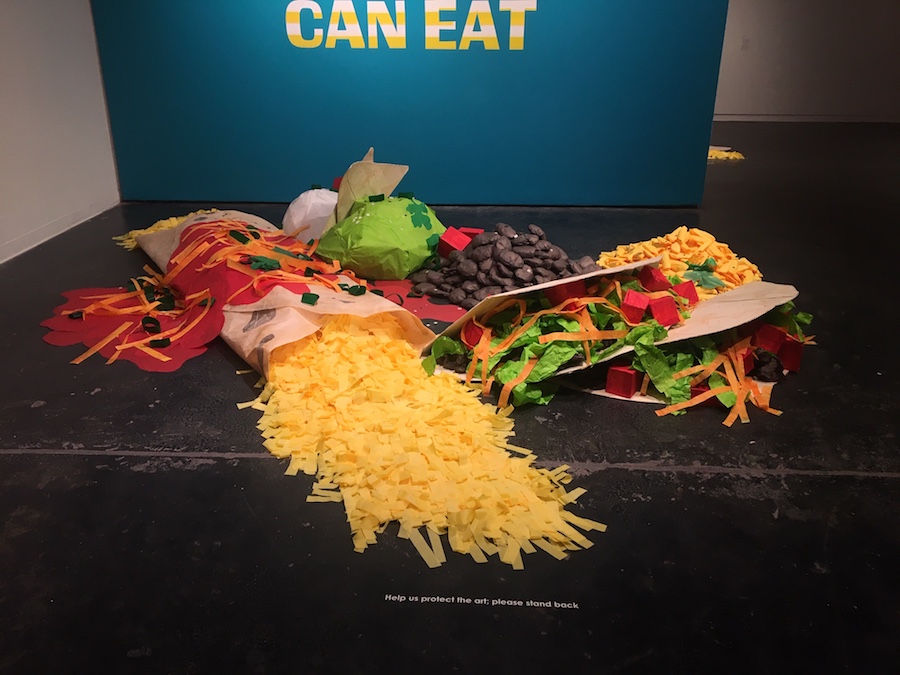

On that note: Justin Favela’s exhibition All You Can Eat at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft sifts through the complications, appropriations, and mutations of what is most Texans’ favorite food group.

Favela also navigates social critique in accordance with, in my view, a higher standard of criticism (artists like Leslie Hewitt are increasingly and adroitly adopting this tack), which means that he avoids didacticism and instead lovingly exposes various concerns in a multi-faceted manner, and asks the right questions about our complicated relationship with the issue at hand.

In Favela’s case for this show, that issue is cultural appropriation. With All You Can Eat, we are meant to feel satirized and united, critical and connected, excited and a little embarrassed. If going by HCCC’s text for the show, Favela elicits all these things from us through his use of material, such as covering the armatures of his sculptures with the same paper that is used to make piñatas (a uniquely Mexican tradition). While this is partly true, I think that assertion reduces the work to merely communicating conceptually via material. But the show is more than a version of Conceptual Lite; the installation as a whole actually stirs up complicated feelings in the viewer — feelings around complicity and colonialism and shared joy. The piñata paper does some of that, sure, but Favela most effectively gets his point across via scale.

Favela has giganticized everything — purse-sized beans and boulders of guacamole abound — yet these objects still feel diminutive. I think this is intentional. Favela uses swaths of bright colors that make, say, a giant enchilada resonate as childlike and wondrous. He’s enlarged objects that are intended to be manipulated and consumed, and though these meals are clearly inedible, they read as cute and adorable and incite the desire for us to want to aggressively consume them. It’s possible that this possessive impulse tracks with the same desire we have to consume, manipulate, and even condescend to cultures other than our own — in Favela’s case as he points out, Mexican culture.

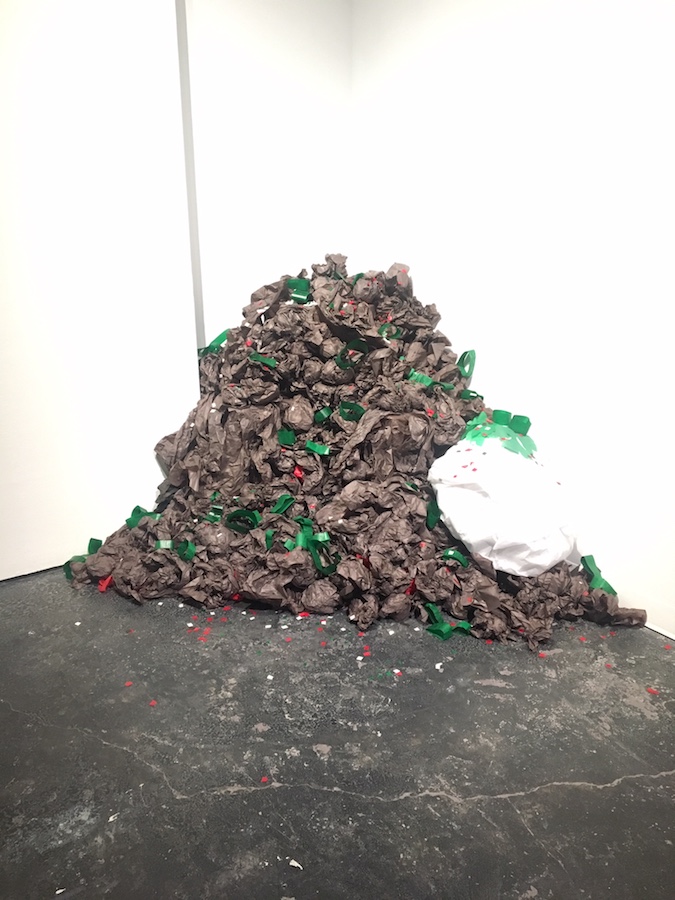

The color palette in All You Can Eat is bold and even simplistic, but there are lovely moments of layered paper that create varied textures. We see this most specifically in Favela’s handling of subtle variations in value among the nacho chips, as well as the crispy brown spots on the tortillas. My only gripe for this show is the placement of the chili con carne in Chili con carne (2019). Piled up in the corner, it reads as curatorially lazy (especially in comparison to the dynamism of Floor Nachos Supreme, 2019) and has that This is What Contemporary Art is Supposed to Look Like feel, a la Beuys and Gonzalez-Torres. Other than that, All You Can Eat made me very hungry for Tex Mex — and I’m not sure how comfortable I am with that.

Through September 1, 2019 at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston