By Michael McFadden

In working with clay, an artist communes with a material tradition that spans thousands of years and stretches around the planet. With each passing decade, the medium becomes more accessible, more demystified, easier for the untrained to manipulate. Yet, ceramics remain an amphitheater from which stories and traditions are shared.

While other mediums carry certain historical baggage that weighs them down, the versatility found in clay connects cultures across imagined and fabricated boundaries. Over the course of his storied career, ceramicist James C. Watkins, who lives and works in Lubbock, has spent decades learning and mastering skills of the craft and implementing them in his practice.

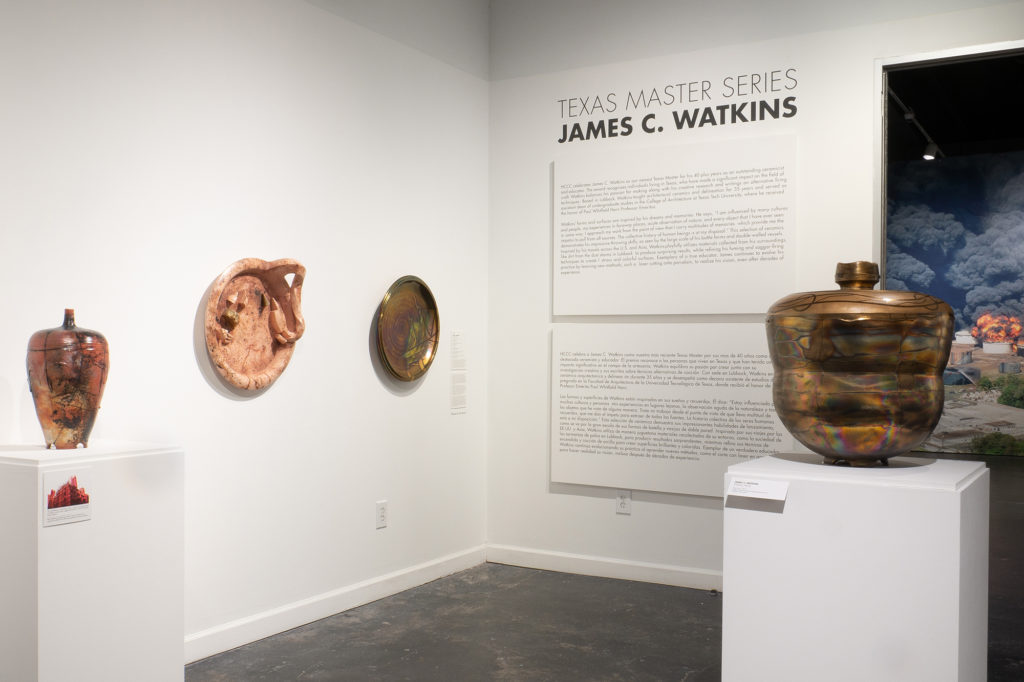

On view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (HCCC) through May 8, 2021, Texas Master Series: James C. Watkins honors the artist for his dedication to his craft. While the exhibition focuses on more recent works, it showcases the breadth of Watkins’s career and the diversity of his skill and inspiration.

Place, history, culture, architecture, and dreams are on display throughout the exhibition. Each piece shares a story which links Watkins’s career to different locales. Within the show, references to cultures, countries, and companions trace a map of his time as a scholar and educator. Two Japanese tea bowls refer to the artist’s time in Hakone, Japan; they are an appreciation of tea as a daily ritual and a celebration of the kinship formed with his fellow artists. In Platter from The Fragility Series (2005), the artist reflects on his visit to Angkor Wat. Lines in the coloring form cracks in the structure as separated segments reflect the fractured history of the area. The familiar face of Buddha emerges, his ancient eyes peering out into space.

Watkins’s appreciation for architectural feats likely stems from his split career. As an educator, he established himself at Texas Tech University both as a ceramics instructor as well as a core teacher in the school’s college of architecture. Through his teaching experience, there was a strong connection between architecture and the fine arts. A draftsman is able to map out structures to a fine point. Watkins knows this well, as he taught architectural delineation for thirty-five years and published books on the subject.

Today, Watkins sees less and less of the connection between art and architecture as the latter places a growing emphasis on digital work, lasercutters, and 3D printers. Reminiscing during an interview with Glasstire, he stated, “I taught watercolor, free-hand drawing, architectural ceramics, and figure drawing as part of architecture.” Technology has changed that relationship drastically over the course of Watkins’s career. However, Texas Tech recognized the importance of his studio work and allowed him to practice his art as the research component of his professorship. Watkins is skeptical about the translation of analogue techniques into digital environments. He reflects that “today, there is a small portion of drawing incorporated into design courses, but in my opinion that is something like skim milk drawing.”

Combining the deep historical references of clay with its transformative potential, Watkins’s techniques reflect his connection to the earth, as he was raised by farmers. The carved surfaces of his pots are marked with the plowed furrows of freshly tilled farmland. After a visit to Rattlesnake Canyon in Texas in the late 1980s, he similarly began incorporating materials from canyons and deserts to color the surfaces of his pottery.

Lubbock’s dust storms inspire and participate in Watkins’s work: he regularly collects the dust these weather events leave behind and incorporates it into his pieces. The land of the Llano Estacado itself is one of his materials. Manipulating the color through a variety of firing techniques, Watkins attains deep blacks and reds that evoke these western lands.

Using these time-honored processes, Watkins elevates their connections and draws attention to their history. Ceramic structures play a key role in the history of this region, with Indigenous use of the material dating back at least to 500 BC.

Today, ceramics has advanced far beyond its initial use in pottery and structures, covering anything from kitchen floors to the surface of the space shuttle. Watkins’s works are constructed with the artist’s expertise honed through decades of research. Yet, the visuals offer a connection to histories and cultures that extend far beyond form. In his Painted Desert series, for example, the artist draws inspiration from both the land and Indigenous pictographs found along the U.S.-Mexico border. A swirling blue evokes imagery left behind on the land, just as the cracked, pockmarked texture of the platter mirrors the erosion in the region.

Dreams hold great influence over Watkins’s practice. Attesting in an interview with Glasstire that he feels much smarter when he’s dreaming, he credits the signature form of his double-walled vessels to a lucid dream. Mimicking the form of a cauldron, the artist recalls first experiencing the form in a dream where the works were already on display in a gallery. From a thorough mental examination of the pot, he reverse-engineered the style and began crafting.

Double-Walled Cauldron from The Horizon Series (1985), perhaps, provides one of the greatest cross-sections of the artist’s inspirations. The robust structure of the cauldron lends credence to the durability of both the medium and the land from which it draws influence. Yet, the eroded texture and the delicate coloring bring a softness to the piece.

Among his most recent works on display are two, each titled Bottle Form, from a series titled Fumed, in which Watkins plays with the luminescence of a gold luster. Centrally located in the exhibition, light pours over and from these pieces. Seen as deep black from an angle, the finish gives way to the lustrous gold, only to later invoke a cascading rainbow. These forms are vivid, energetic, and memorable.

Through a versatile collection of styles, techniques, and inspirations, Watkins has built a career that showcases the potential of his medium. His aesthetic vocabulary emerges from personal and borrowed histories, and his body of work operates as an archive of preserved memories.

From the amphitheater of his pottery, on display in Houston at HCCC, he calls upon his past experiences across cultures to speak to the power of tradition, place, and lucidity.

Michael McFadden is an art critic living and working in Houston. He is a graduate of the Arts Leadership MA program at the University of Houston and has worked with regional artists and organizations as an exhibition organizer, grant writer, and marketing specialist. Learn more about him at pugintheair.com.