by Doug Welsh

THIS SIDE UP, curated by Sarah Darro at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, illuminates the often invisible practice of art handling. The exhibition features 16 art handler-artists, with work by core artists Vivian Chiu, Willem De Haan, Clynton Lowry and Adam Manley. Uniquely skilled craftspeople, art handlers (or preparators) pack, ship, handle, move, prep, and install art, consistently meeting demands for precision, efficiency, adaptability, and safety. This rare combination of attributes and skills, though celebrated in many artists, is expected of preparators without recognition. Most major exhibitions are only possible because of the ingenuity of these creative individuals, yet their names are rarely included on the wall next to the artists, curators, and donors. THIS SIDE UP struck a chord with me in part because I’ve worked as an art handler since 2016. I know the care, craft, and rigor required, and I have experienced the ways in which our work can feel unseen.

During a walkthrough of THIS SIDE UP, Sarah Darro shared some insight into her vision for the exhibition and how it came to be. Over the past 10 years, various curatorial roles have necessitated that Darro learn aspects of art handling. Working in this capacity, Darro came to fully appreciate the artistry required of preparators, and her idea for this show has been percolating ever since. It was important to Darro that she mirror the relational networks of art handling communities in organizing this show, where participating artists would recommend others for consideration.

One of the strongest advocates for the art handling community is Clynton Lowry. The conceptual artist is best known for founding and running Art Handler Magazine, a highly visible publication with a large online presence that celebrates and supports preparators globally, calling for better pay and working conditions. Reprinted copies of the magazine’s first two editions are on view in the gallery. In addition, Lowry presents two suspended jackets and a sleeping bag, all fabricated with moving blankets, which are vital to almost every aspect of art handling. The materiality and form of these objects evoke a human presence and serve as haunting reminders of lost labor by skilled workers. With both the magazine and his art practice, Lowry undermines systems of power and exclusion, questioning what and who we choose to value in the art world.

Multidisciplinary artist Vivian Chiu acquired and repurposed dozens of 45 to 80-year-old crates for this exhibition. The crates were a gift from Mei Lum, the fifth generation owner of Wing on Wo. & Co, the oldest continuously operating store in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Chiu deconstructed the crates and reconfigured them into vessels that match the forms of porcelain objects they were originally designed to transport. To facilitate this, Chiu developed a system of making that involves elaborate math (done by hand on graph paper), precisely cut angled units of wood, and careful labeling to ensure the units fit together seamlessly. Chiu’s works are in conversation with several chairs and a coffee table that John Powers and William Powhida fabricated using upscaled art crates. Problem solving, system design, and transformation are essential aspects of art handling, highlighted with works by these artists.

Adam Manley creates reliquaries, which are containers designed to safely support art objects. Where most reliquaries are fabricated for rare and valuable items, Manley creates them for ordinary objects that he thinks should be collector’s items — a dolly, a step ladder, customized hammers, tape measures, or the 20-year-old mop and bucket from the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. His work makes me consider what we value in the art world now, and what will be considered valuable 1,000 years from now, when our current artifacts of industry and culture exist in anthropological museums of the future. I especially enjoyed the moment where John Riepenhoff’s fabricated art handler holds the lid of Manley’s reliquary. This direct interaction between two art objects raises questions about the value of skilled labor in the art world.

In the business of transportation and exhibition design, Willem De Haan created a three-piece luggage set, fabricated in plywood to an airline’s exact size restrictions. It is striking to consider how these art objects would function in different settings — at the airport, they are likely to be thrown around by baggage handlers, whereas in the gallery they are venerated. Perfectly paired with this work is a small Walead Beshty sculpture consisting of a FedEx box supporting a glass cube. The cube fits perfectly into the box and travels from place to place. With no supporting foam or protection, the glass cube becomes increasingly damaged as it travels. This work is poetic, dark, and playful. Any art handler would see the humor in this, as we have all received poorly designed packages with damaged art inside. Both De Haan’s luggage set and Beshty’s glass cube are shaped in part by systems of moving and shipping.

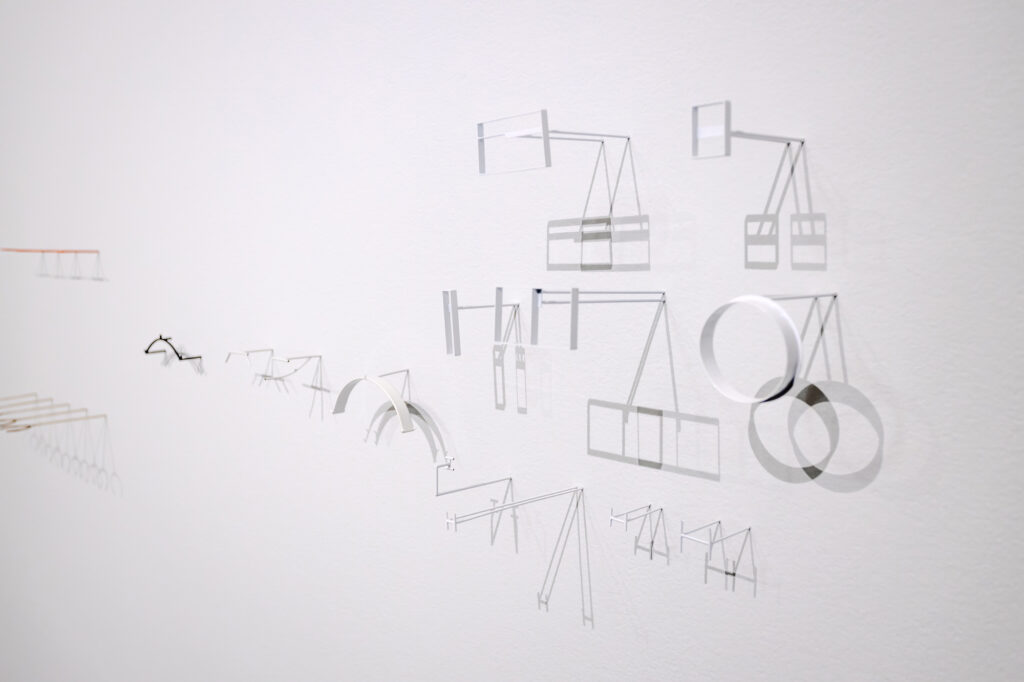

Also illuminated within this exhibition are mounts, carefully crafted objects designed to support artworks and simultaneously disappear. Viewers are not trained to look for or appreciate mounts. Instead, we admire the artwork, which floats, as if by magic. Yet it takes specialized skill and training to create custom mounts such as the ones on display by Jessica Andersen, Galen Boone, Motoko Furuhashi, René Lee Henry, Jessica Jacobi, Seth Papac, Demitra Thomloudis, and Bohyun Yoon. In this exhibition, mounts are celebrated as strange and fantastical works of art in their own right.

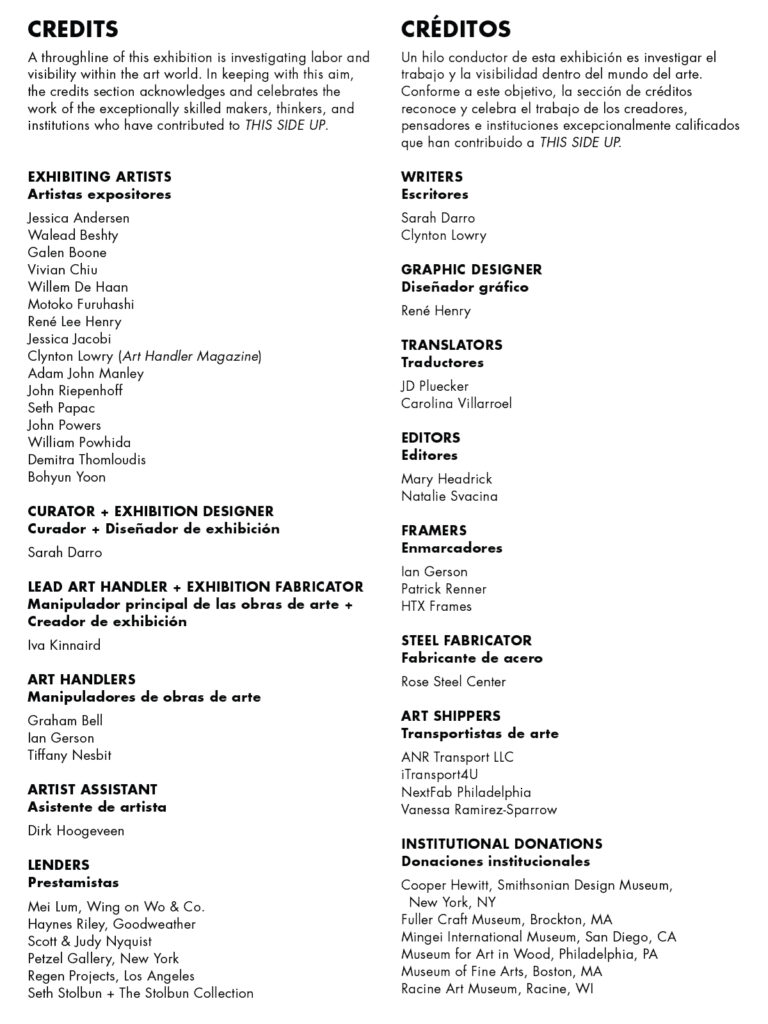

THIS SIDE UP weaves together conceptual art practices, masterful fabrication, creative reuse, problem solving, and specialized skill sets, highlighting the passion, craft, and ingenuity of art handling. Sarah Darro and these 16 artists reveal the magic happening backstage that most people are not permitted to see. Importantly, every skilled worker involved with the exhibition was acknowledged in a comprehensive credit wall, which I believe should become the norm for all art institutions. THIS SIDE UP brings much-needed visibility to art handling communities, and hopefully will be a catalyst for a more equitable art world.

THIS SIDE UP is on view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft through May 4, 2024.