In the spring of 2019, HCCC intern Kelly Dolan interviewed former resident artist, Ean Escoto. As a jeweler and metalsmith, Escoto presents a new style of craft that takes the concept of jewelry into the contemporary aesthetic. Escoto, by incorporating roboticics into his designs, makes exceptional work that conveys a sense of meaning and whimsy to his audiences.

Kelly Dolan: You initially went to school to study bioengineering; however, you graduated with a degree in applied design for jewelry, metalsmithing, and ceramics. How has bioengineering influenced the combination of electronics and jewelry in your work, and what other influences inform your work?

Ean Escoto: I would argue that art and science are born of craft; art and science were predated by craft as disciplines while present within craft as practices. Bioengineering and craft, particularly art jewelry, both satisfy my core interests, providing people with something meaningful. Bioengineering generally seeks to enhance people’s quality of life by supporting their physical needs. Craft tends to focus on the impact of objects of daily use on people’s lives. For me, they both start with the body.

Jewelry objects are literally attached to the body as items of use or metaphorically attached as items of consideration. Most often, they serve as prostheses of identity, evoking meaning for the wearer and the viewer. I find this platform for expression really great for the types of engagement I would like to have with others.

Science and engineering have greatly informed my approach to living with appreciation and curiosity. Science is a formalization of the fact that the natural world will answer any question you ask it. The challenge of science is in the difficulty of understanding what you actually want to ask, learning how to phrase it, and interpreting the answer you receive. The glory of science is that the answers we receive spawn even better questions. It really seems like the universe will never run out of wonder. Engineering provides a powerful set of problem-solving tools. The basic idea is to break a problem into smaller parts that you either understand or don’t understand. You solve the parts you understand, quantify what you don’t understand, and use that information to find or create resources which will allow the problem to be solved.

When I make jewelry, I apply the tools I have to solve the problems I am interested in. The initial motivation behind introducing electronics to my practice was to make objects activate people’s theory of mind. I wanted people to consider what the object is thinking. This ability to consider the thoughts of another is worth celebrating. Leveraging this experience is a powerful tool for getting people to engage in the other types of experiences I am trying to promote.

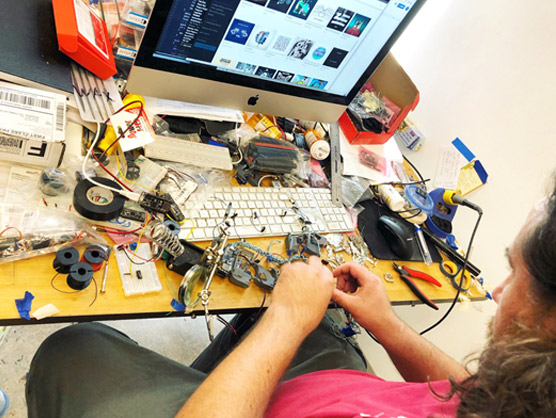

KD: The design behind the electronic elements of your jewelry requires an understanding of coding, an integral part of creating software. The use of coding is typically associated with the development of computers, apps, websites, etc.; however, in your work, you use code to evolve your creations and bring them to life. How does your programming contribute to your overall aesthetic and the transformation of your craft? Why is it important for the hardware of your work–the wiring, computer parts, etc., to be exposed?

EE: I don’t know how to present the craft of code. In my work so far, the hardware determines what is possible, and the software expresses some behavior within that possibility space. The programming is an important part of the object, but the structural and aesthetic decisions made writing it are rendered invisible. I guess it is similar to other fabrication processes which don’t necessarily announce themselves in the final form.

I program the microcontrollers in the Arduino environment, which is a version of the C++ language. I try to follow the Arduino style guide, which is beginner oriented. Most style guides focus on supporting collaboration, making your code legible and accessible to someone else. When I encounter the necessity or opportunity to collaborate, I want to be a good partner.

It goes against my instincts to hide components. I want every part of my jewelry to contribute to the whole piece. Why work with found objects yet put them all in a black box? I feel that would also work against my efforts to reward curiosity and exploration. Being constrained by parts manufactured without regard for my application or aesthetic is frustrating. However, it is my challenge to apply them in a way which supports my purpose.

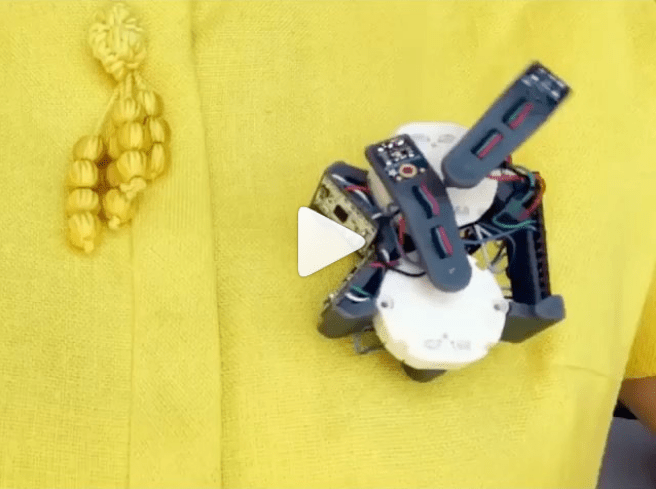

KD: Your work engages with its audience as much as it engages with its environment. For example, you made a brooch that responds to light in its surrounding environment. Why did you design this piece to respond to light, and what does this interaction mean to you?

EE: The brooch has a pair of light sensors, each mounted to movable arms. Each sensor scans around for and then points at the brightest source of light that it sees in the room. One sensor uses a gradient descent algorithm, and the other uses binary search. Their different algorithms produce different motions in order to evoke different personalities. As the lighting conditions change, the sensors reorient themselves to the new brightest source.

It is interesting to me that the movement of the wearer, the condition of the environment, and the internal state of the brooch combine to determine the object’s behavior. The way that measuring the intensity of light collapses these entities reminds me of how fuzzy the boundaries are between person, tool, and environment. People and tools are part of the environment. When do things like your heat, breath, or cells transition from being a part of you to not? The mind is a product of the body and environment. Tools extend the mind and the body, enabling different conceptions of and interactions with the world. In this way, I would classify every tool as a prosthesis.

For me, the most important aspect of the brooch in the environment-person-object system is the way that it catalyzes interaction. Because the brooch has its own motivation, it reaches out to engage the viewer. It breaks the barrier by making the first move. After that, the brooch serves as the seed of discussion. Hopefully each party enjoys the conversation. Through this dynamic, I am trying to promote curiosity, exploration, and exchange.

KD: Jewelry is a means of self-expression and, over time, makes a gradual journey as it is worn by and passed on to different people, whether they be relatives, close friends, or even collectors. How do you see yourself, as a maker, interacting with the wearers of your jewelry? What about this form of engagement is meaningful to you?

EE: I am mindful of the lifecycle of objects. I want my jewelry to live beyond my hands. Energy must be expended on an object for it to live. For someone to continue investing energy into my jewelry, they need to get something out of it. This is part of why I try to make my jewelry experientially valuable, to reward people’s interactions with the objects as wearers and observers. I want to help people express something about their identity while simultaneously nudging it in a certain way. I want a passerby in the street or in the gallery to get caught for that extra moment that leads to further engagement and possibly to a shift in perspective. I try and hitch my jewelry to people’s curiosity, sentimentality, personal identity, psychology, social interaction, and aesthetic pleasure.

People integrate jewelry into their lives, imbuing the objects with history and sentiment. With my series of brooches that hold rings, I try to feature this aspect of the wearer’s ring collection.

One opportunity to enhance the way that the wearer develops a relationship with my jewelry is to make jewelry which grows with use. It could learn from the wearer and adapt itself to them. In this manner, a number of people could start with identical pieces that would diverge through individuated experience.

KD: Most of your work is intended to be worn; however, you also create vessels. Where do these fit into your artistic practice? Do you feel that either body of work informs the other?

EE: Vessels are great objects of use with a looser connection to the body than jewelry. People relate to them in a personal way. The concerns of vessels are a little different from those of jewelry. This shift in perspective and constraint has proven to be fertile for me. It has resulted in new techniques and materials for both my jewelry and vessel making.

About Ean Escoto

Ean Escoto works in jewelry metals, incorporating fabrication, casting, ceramics, 3D printing, and electronics. He believes that jewelry accrues sentimental value as it is carried through life events, and he wants his jewelry to be a participant in people’s lives. His work always provides the wearer with a small story or mystery to share. Whether derived from studies in materials, technique, or interaction, his pieces shrink the gaps from plinth to hand and person to person by rewarding curiosity and investigation.

Ean was raised in the small, picturesque town of June Lake, California. He moved to San Diego to study bioengineering at the University of California, San Diego, but he graduated from San Diego State University with a BA in applied design for jewelry, metalsmithing, and ceramics in 2016. Ean is a 2016 Windgate Fellow. He has been a partner in a private studio for five years, and his work has been shown in Taboo Studio, San Diego, CA, and Galerie Marzee, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. During his time at HCCC, he worked on jewelry that expresses its motivations and goals through electronically controlled movement, as well as the accessible side of his jewelry line. To learn more, visit https://eanescoto.com/