My first visit to Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (HCCC) was only a few years ago, on one of my regular trips to Glasstire’s HQ. Ever since then I try to stop in every time I’m in town — often more enthusiastically than my visits to the MFAH, or CAMH, or the Menil: Houston’s triumvirate of high-art hitters.

I gravitate to HCCC despite my own bullishness regarding art and craft as separate worlds, but I think that’s a testament to everything HCCC gets right. In its very reason for being, it defies categories and lets the definitions of craft and art and even social practice interweave (as it were) and the results tend to consistently surprise and charm me. Maybe the word “Craft” in its name helps me walk into the building without expecting a life-changing or mood-altering experience — something the hallowed rooms of art museums seem to promise but often fail to deliver — and so when I see the HCCC’s shows (and its resident artists’ work installed in an adjacent section), I feel not only satisfaction, but often also relief. The work does what it’s meant to do, whatever that may be in that space on that day. I leave in a spry mood and the world seems to make a little more sense.

Maybe this is something craft and design can do for art. Craft’s very groundedness can, when working in concert with art ideas, bolster and enhance the art aspect, and make the whole sing more clearly, the way good use of language can bolster a philosophical thesis, or good engineering can better deliver an architectural impulse.

One of the first HCCC shows that really stuck with me was the work of three military war veterans who used craft (and an attendant kind of art) as a therapeutic practice to deal with their trauma. One of them, Ehren Tool, a Gulf War Marine, showed a wall of shelves lined with pottery cups he’d done on a wheel, and press-molded military and war emblems onto. More craft than art, but pretty dark in that plenty of the imagery was violent, or grief-stricken, or both. And yet then on the adjacent wall was his video that slyly strayed into art’s trenches: it showed a loop of his cups being pierced or blown apart in real time by single bullets: a tiny ballet of destruction. I watched it for ages.

Ehren Tool, in the show ‘United by Hand: Work and Service by Drew Cameron, Alicia Dietz, and Ehren Tool” at HCCC in 2017

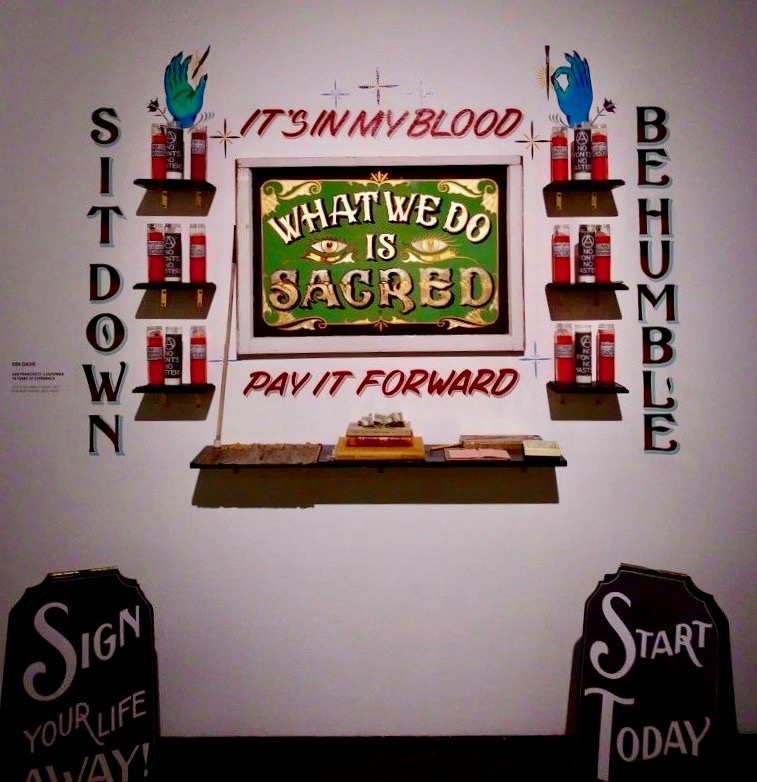

The curatorial bent of HCCC feels playful and open. A 2018 exhibition that showcased the work of contemporary sign makers and sign painters still working in traditional ways grew over the four months it was up, as some of the artists created and completed their murals and banners and sandwich boards in the gallery. While it’s nothing new to have an institutional show evolve or change during its run, this tack suited this particular show better than most, and actually made sense. Over time, the space grew fuller and more colorful and graphic and jumbled, so that by the end it was like walking into a Looney Tunes landscape of road-trip Americana.

Emerging artist discoveries feel great in any venue, but Melissa Cody’s show of woven textiles at HCCC in 2017 left a big impression on a lot of people. A fourth-generation Navajo artist and weaver, Cody’s designs seemed to singlehandedly create a whole new strata of the ultra-traditional meeting Right Now: she embraces and eschews tradition with a deftness I haven’t associated with textile artists working with dyed wool on a loom. The pieces were gorgeous and funny… and pretty provocative, actually, which is something that transcends much of what I tend to believe about craft. Since then, I’ve seen her name cropping up repeatedly in reviews and publications announcing her arrival as one of the best textile artists working today. I agree.

HCCC hosts a lively artist residency, and the artists work out of small studios in the building during open hours. Visitors are encouraged to go take a look at what’s cooking and engage with the artists. Late last year, I made a mistake of thinking I was meant to leave them the hell alone: after all, they’re working. I was with Glasstire’s Brandon Zech that day, and I started drooling over some ceramic-bodied, bulby legged lamps with lightbulbs for heads installed in the hallway outside the studios. I took too many pictures. The artist, Jenny Mulder, was about 12 feet away, through a half-open door, working away in her studio. After we left and I told Brandon how much I liked the work, he said: “Why didn’t you ask her about them?” I must have looked confused. He added: “That’s why the artists are there. So you can talk to them.”

I was at HCCC two nights ago, to catch part of a performance art festival (Experimental Action) going on in its parking lot, but the shows inside called to me first. The functional ceramics in the front gallery by the small studio East Fork, out of North Carolina, were so lovely I nearly had to punch myself to keep from touching them. This is craft — the best sort, that reminds you of how satisfying it is to live with (and use) traditionally handmade objects. The bigger main gallery has a show on of work by the Wisconsin-based artist-designer Tom Loeser. It’s a traveling show, co-orgainzed by HCCC and the Museum of Craft and Design in San Francisco. One interactive feature encourages you pick up and roll and sit on and stack Loeser’s ridiculously fun (and beautifully made) felt-inlaid wooden crates, with handle holes. I knew I was meant to be out in the parking lot, but in that moment, as I lolled around on them like they were large friendly dogs, all I was thinking was: I need these in my life. The art in museums can do this to me too, but not often, and not at all with the batting average of HCCC. There’s no other place like it in Texas.