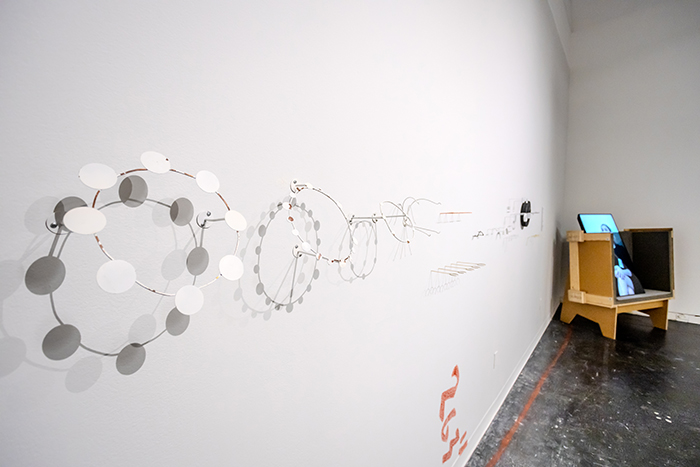

If you’ve ever visited an exhibition and wondered how an artist pulled something off, chances are good a preparator had something to do with it. The behind-the-scenes part of the art world often goes unnoticed or unremarked upon due to the nature of the job, but legions of handlers, fabricators, preparators, and conservators as well as artists themselves toil to make exhibitions possible.

On view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft through May 4, 2024, THIS SIDE UP centers the specialized knowledge and problem-solving skills involved in art handling and care within the field of craft—“an exhibition about the making of an exhibition.”

“I am in the unique position of being a curator who has also worked behind the scenes as an art handler, exhibition fabricator/preparator, and textile conservation assistant,” said Sarah Darro, Curator and Exhibitions Director at HCCC. “For the past almost decade, I cobbled together contract art handling gigs in collectors’ homes or in arts institutions and my last role before returning to Houston Center for Contemporary Craft as Exhibitions Director and Curator, I worked as the in-house prep, art handler, and gallery manager at the Center for Craft in Asheville, NC.”

Through these experiences, Darro witnessed the amount of knowledge and craftsmanship that supports the infrastructure of the art world while often hidden from the public eye.

“I wanted to stage an exhibition that was almost inside out, where the masterful creative production conducted in service of art—from crate building and mount making to preparation, art handling, and exhibition fabrication—were visually prioritized and celebrated,” she explained.

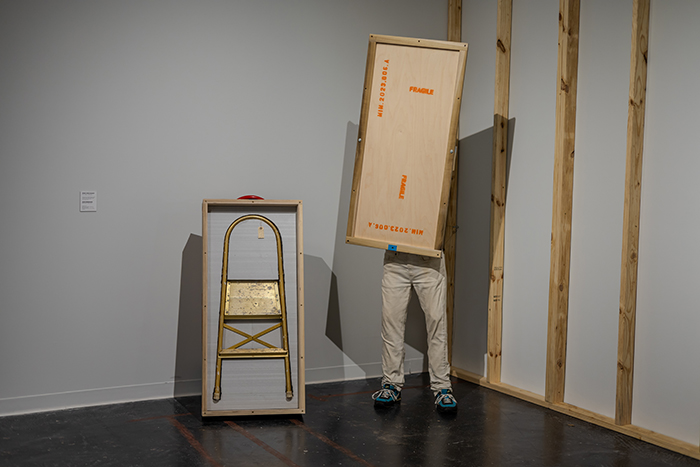

In execution, the exhibition exudes a dry humor about the art world. The galleries appear stripped bare of their white sheetrock, studs on full display; the tools of the trade are presented with the same level of care with which an art handler might crate a piece.

“I was intentional about working in close collaboration with the exhibiting artists to hone in on a presentation style that did justice to the self-reflexive nature of the concept,” Darro explained with artist Vivian Chiu as a core example.

Chiu’s practice involves a methodical dismantling of crates from Wing on Wo & Co., the oldest continually-operating storefront in Manhattan’s Chinatown. She reforms the materials in Passages (those that carried us), a series of vessels adorned in Chinese and English script that share the travels of the porcelain imports they once housed. For the exhibition, Darro and Chiu installed the vessels atop and within the crates from which the materials were gathered.

Other bodies of work within the exhibition similarly highlight the creative reimagining of art crates.

“William Powhida and John Powers continue the long tradition of upcycling the primary byproduct of the art fair or exhibition—the crate—into a living room set of chairs and a coffee table,” Darro shared. “Adam John Manley, on the other hand, is a fine woodworker and furniture maker who specializes in and teaches reliquary-making. He thinks of artwork crates as ‘utilitarian reliquaries’ and in his Quotidian Relics series in the exhibition, he applies the extraordinary level of care usually reserved for works of art to the mundane objects that form the invisible infrastructure of art spaces.”

The exhibition features several of these finely crafted containers for a range of materials, including a framing kit from preparators at the Racine Art Museum and painted tape measures from the 40-year lead preparator of the Cooper Hewitt.

Through these works, he “asserts that the material culture and creative production of unseen art workers are as valuable as the works of art they care for,” Darro explained. “But he also articulates that part of the impetus for making them and crafting perfect voids for each object to fit into was to do a service for the art handlers who might have to receive the works.”

“William Powhida and John Powers continue the long tradition of upcycling the primary byproduct of the art fair or exhibition—the crate—into a living room set of chairs and a coffee table,” Darro shared. “Adam John Manley, on the other hand, is a fine woodworker and furniture maker who specializes in and teaches reliquary-making. He thinks of artwork crates as ‘utilitarian reliquaries’ and in his Quotidian Relics series in the exhibition, he applies the extraordinary level of care usually reserved for works of art to the mundane objects that form the invisible infrastructure of art spaces.”

The exhibition features several of these finely crafted containers for a range of materials, including a framing kit from preparators at the Racine Art Museum and painted tape measures from the 40-year lead preparator of the Cooper Hewitt.

Through these works, he “asserts that the material culture and creative production of unseen art workers are as valuable as the works of art they care for,” Darro explained. “But he also articulates that part of the impetus for making them and crafting perfect voids for each object to fit into was to do a service for the art handlers who might have to receive the works.”

The repurposing of handling materials extends to the series Sleeper by Clynton Lowry—founding editor of Art Handler magazine. Each piece is a wearable editorial made from moving blankets, and the series netted Lowry relationships with prominent fashion designers.

Walead Beshty also sheds light on hidden systems of labor, with the FedEx® Kraft Box series. For these works, “laminated glass cubes fabricated to fit FedEx’s proprietary dimensions are shipped to galleries around the world in their corresponding cardboard carriers,” Darro shared. “They accrue meaning—as well as impact fractures and collaged shipping labels—through transnational movement.”

The result is sculptures displayed as cracked vitrines placed upon cardboard pedestals coated in airway bills. In a show dedicated to the investigation of labor’s visibility within the art world, Darro provides visitors an opportunity to appreciate the craftsmanship and care that make these experiences possible.